1907

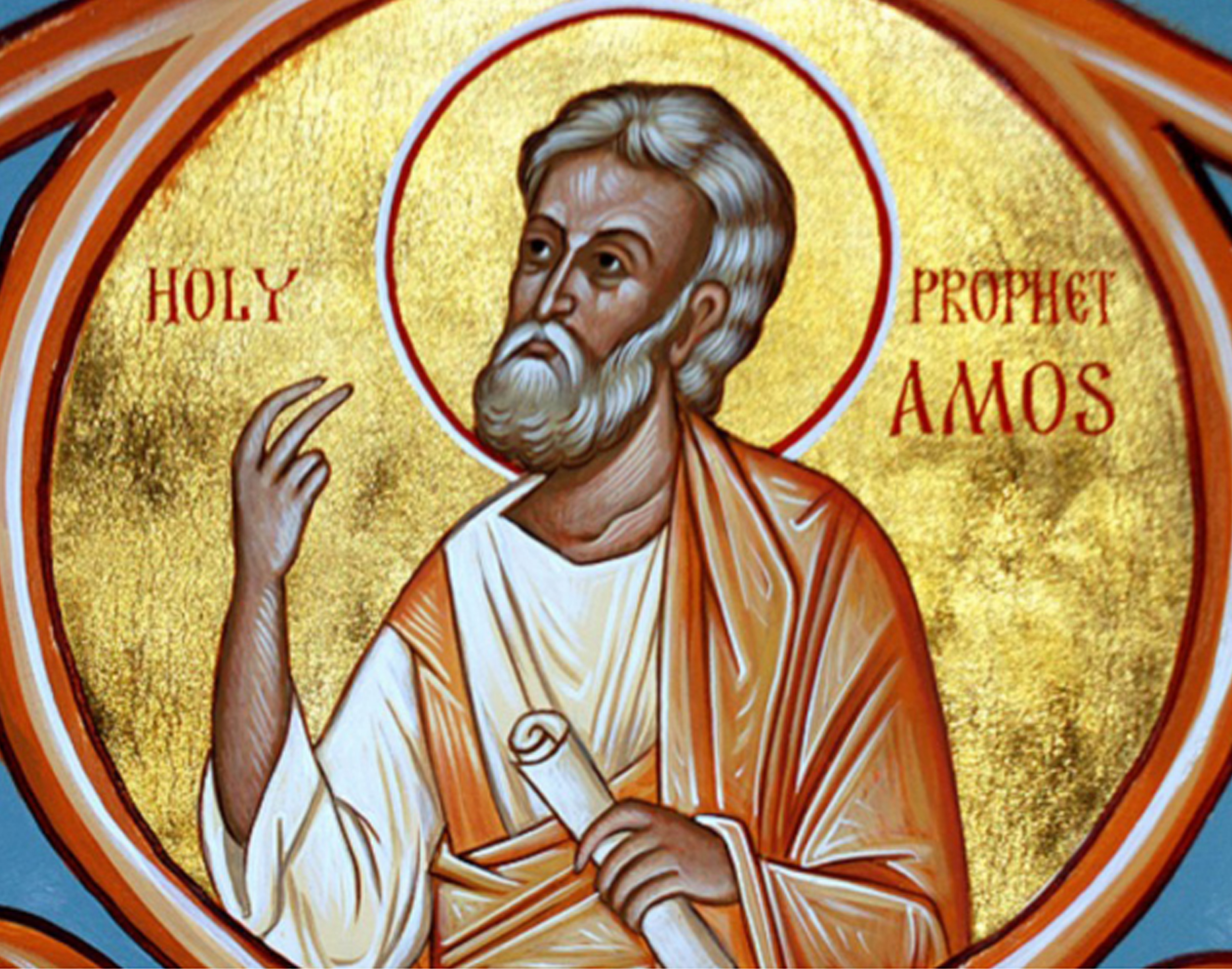

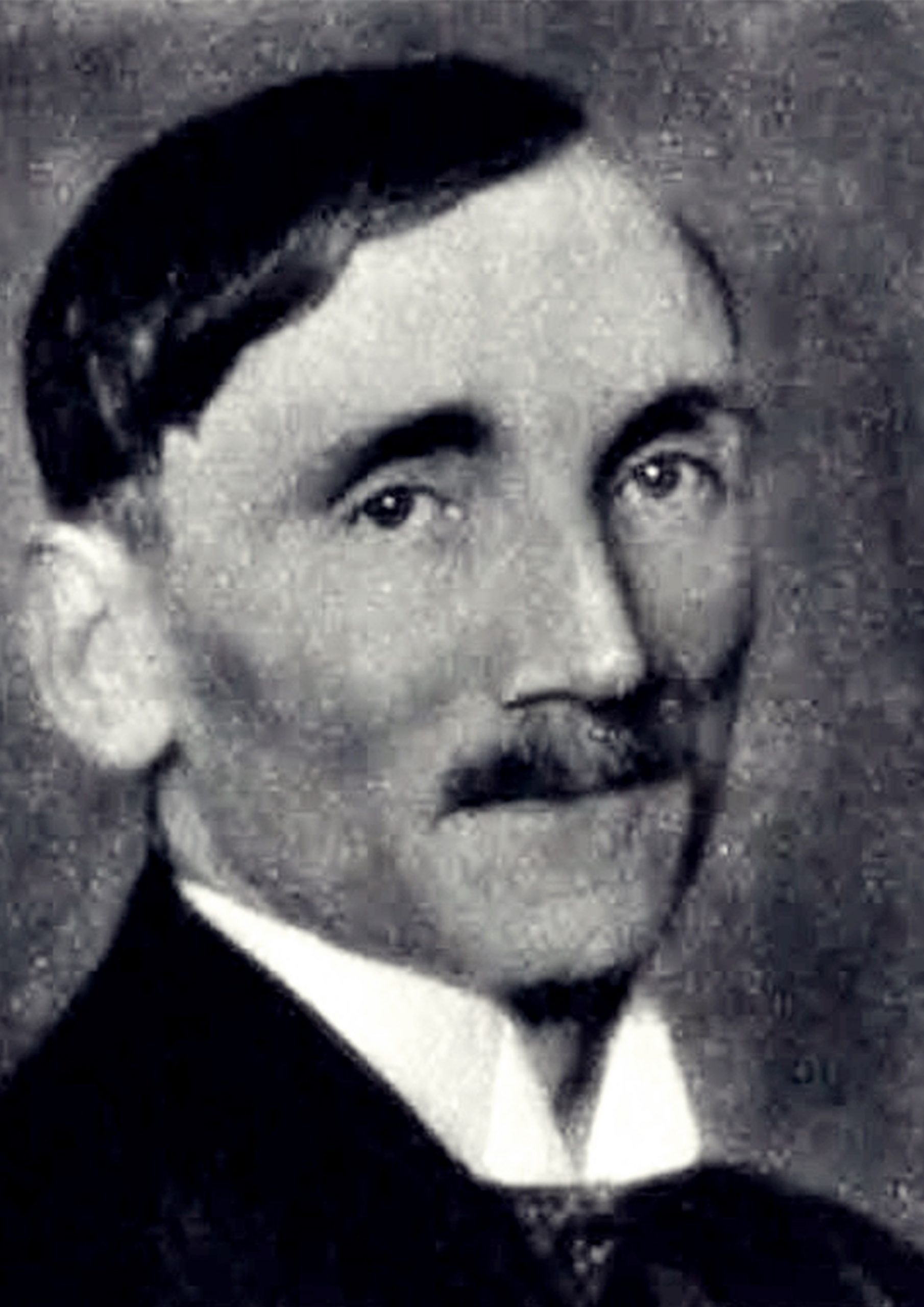

He was born Imre Ungár on the 7th of December in Nagykálló, Borsod county, a place with a significant Hasidic Jewish community who had settled there in the 18th century.

Between 1927 and 1929

He was a student of the predecessor of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics.

Between 1929 and 1935

He was a student of Gyula Rudnay at the Royal Hungarian College of Fine Arts. In 1929, he adopted the name Imre Ungár Ámos after the name of the prophet Amos.

1931

He participated in his first exhibition at the Spring Salon of the Szinyei Society.

1933

He received the commendatory recognition of the Salon.

1934

He officially changed his surname to Amos. He was elected a member of the Munkácsy Guild.

1935

He married the painter Margit Anna, with whom he organized a joint exhibition at the Ernst Museum in the same year.

1936

He was elected a member of the New Society of Fine Artists (Képzőművészek Új Társasága; KÚT.)

1937

He and his wife spent three months in Paris, where they also visited Marc Chagall.

1938

He became a member of the National Salon (Nemzeti Szalon), an association of Hungarian artists and patrons of art.

Between 1938 and 1941

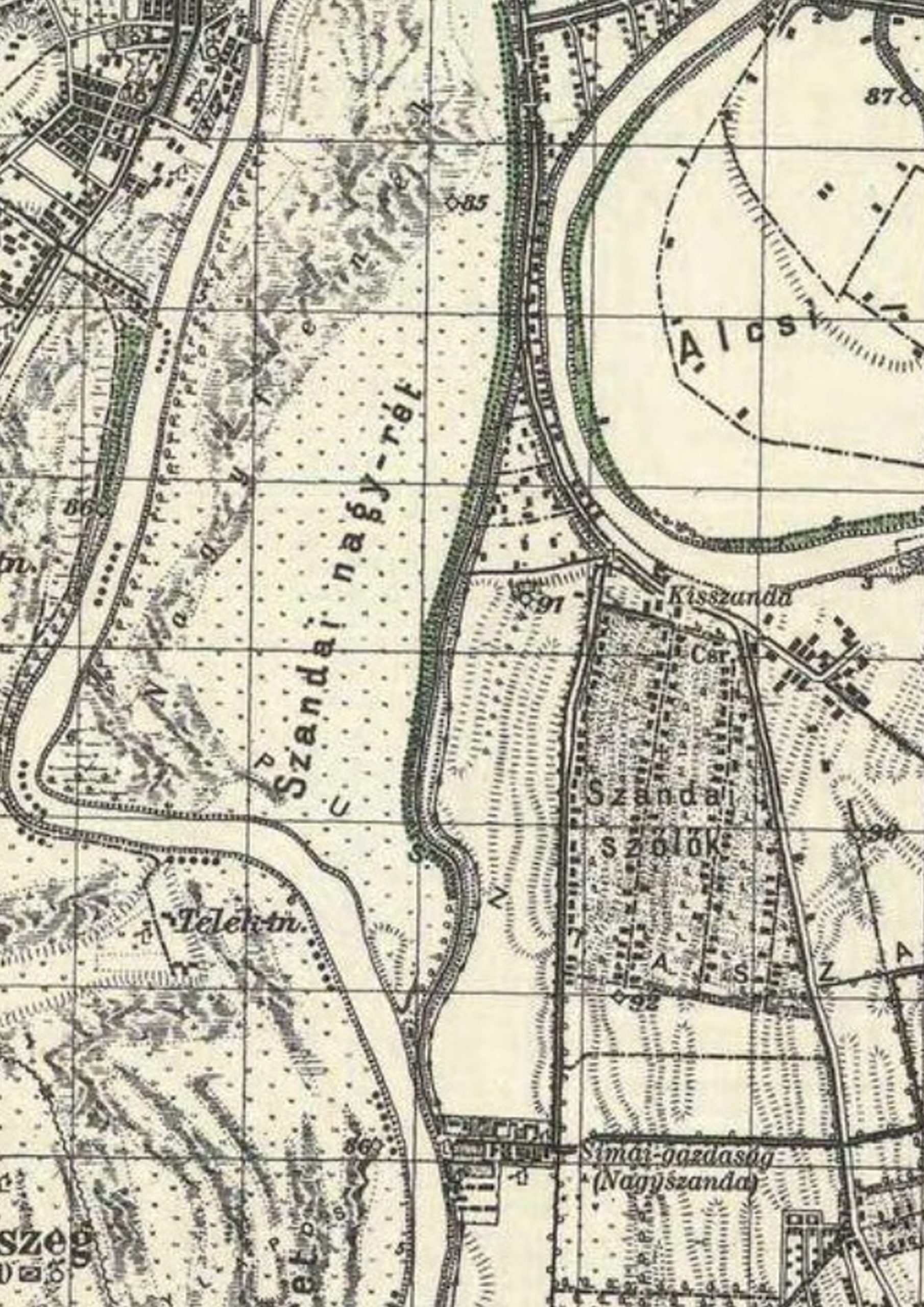

He regularly spent the summers with his wife in Szentendre, where they belonged to the circle of friends of Dezső Korniss and Lajos Vajda.

1940

He created his linocut series 14 Holidays.

Between 1940 and 1944

He was a Jewish forced labourer in Délvidék (the Southern part of the Kingdom of Hungary) and then on the Eastern battlefield with minor interruptions.

In the winter of 1944

He is believed to have died in a concentration camp in Saxony, at the age of only thirty-seven.

1958

A commemorative exhibition was organized in his honour at the Hungarian National Gallery, and his pictures were also presented in Szeged, Pécs and Győr.

2013

A commemorative exhibition was opened at the Hungarian National Gallery titled Imre Ámos, the “Hungarian Chagall” in the whirlwind of war 1937—1944.

The way he became Imre Ámos

He was originally born Imre Ungár, but he never liked his surname. He considered himself to be “sleepy in nature” as a teenager (’álmos’ in Hungarian), therefore he signed his early paintings as Imre Ungár Álmos. He first changed his name Ungár to Álmos in 1931. In 1935, he finally decided to use the form Ámos, with which – as mentioned in one of his poems – he also wanted to express his “kinship” with the biblical prophet Amos. The name change is also a gesture of rebirth/change and finding his identity.

He resigned himself to his fate

Although he no longer followed religious regulations as an adult, he cared about Jewish cultural traditions throughout his life. The inhuman and exclusionary anti-Jewish Laws made him defiant. He had hardly any paintings and graphics without typical Jewish objects and figures. He returned home from his third forced labour experience after a great deal of suffering and began painting again. After that, he was taken again two more times. His friends and wife tried to convince him to try to escape or find a hiding place, but he replied, “everything shall go as the water flows”.

Exemplary, tormenting love

In his wife, the painter Margit Anna, he found not only a companion, but also a friend who understood his art and human weaknesses. After just a few days of acquaintance, it became evident that the two young painters would be together. His wife’s unconditional love and support accompanied Ámos throughout his short life. During their career, they drew and painted many pictures of each other, but their close connection is mostly revealed in their finely drawn double portraits and love correspondence.

”It has been so long since I saw you, as if years had passed, nothing and no one could make up for you, you belong to me as if you were a part of my body that I do not feel right now.” (1932)

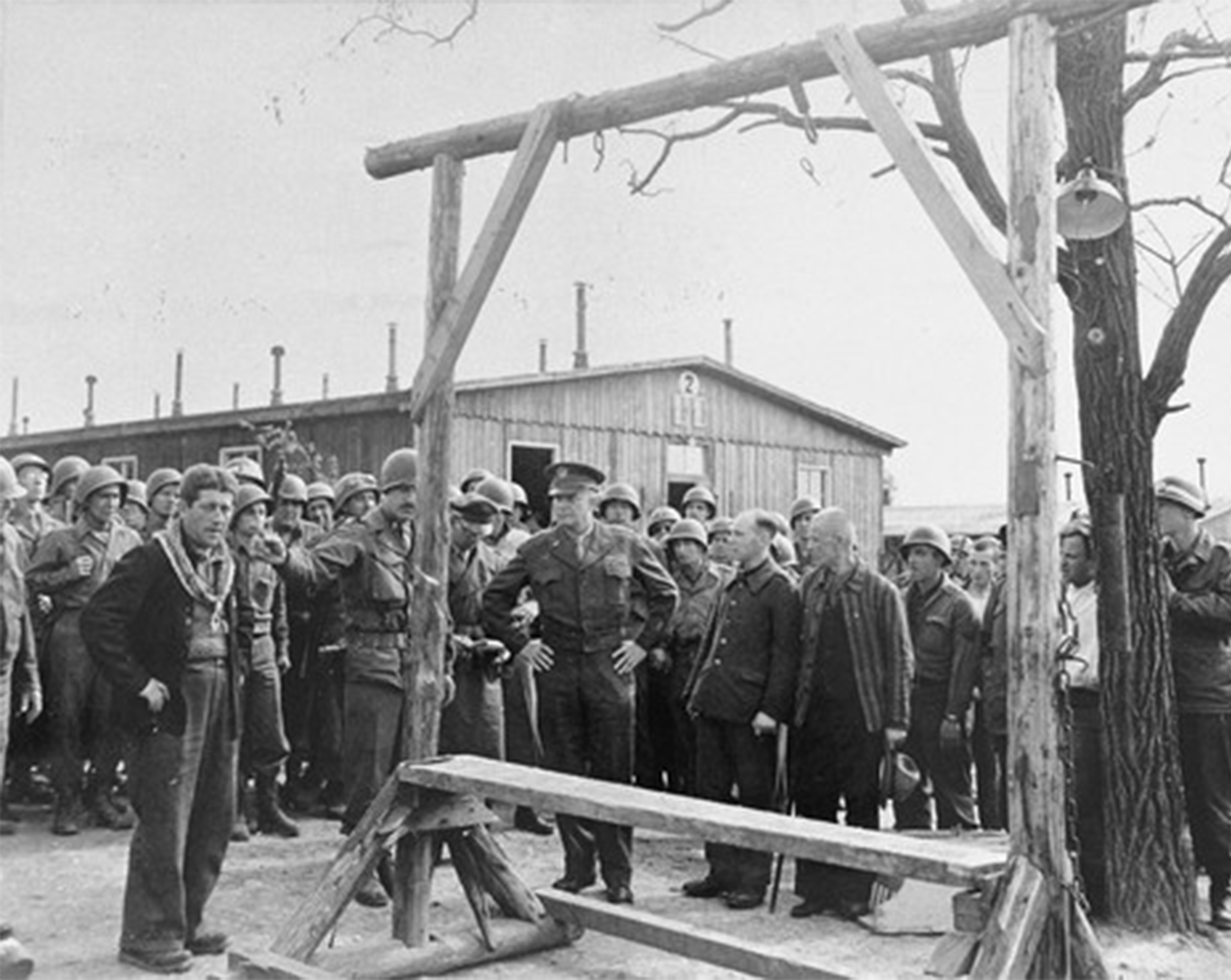

The unknown end to a tragic life

During the Second World War, Imre Ámos was in forced labour camps with just a few interruptions: he was in the Ukraine in 1942–1943, then in Szolnok in 1944, from where he was transferred to a concentration camp in Germany. The last news about him was that he was seen by his fellow prisoners, already sick in the Ohrdruf-Nord concentration camp near the Thuringian town of Ohrdruf, Germany. Amos certainly died somewhere in Germany at an unknown place and time, a few months after last meeting with his wife in Budapest for a few minutes. Margit Anna was never able to properly bury her husband.

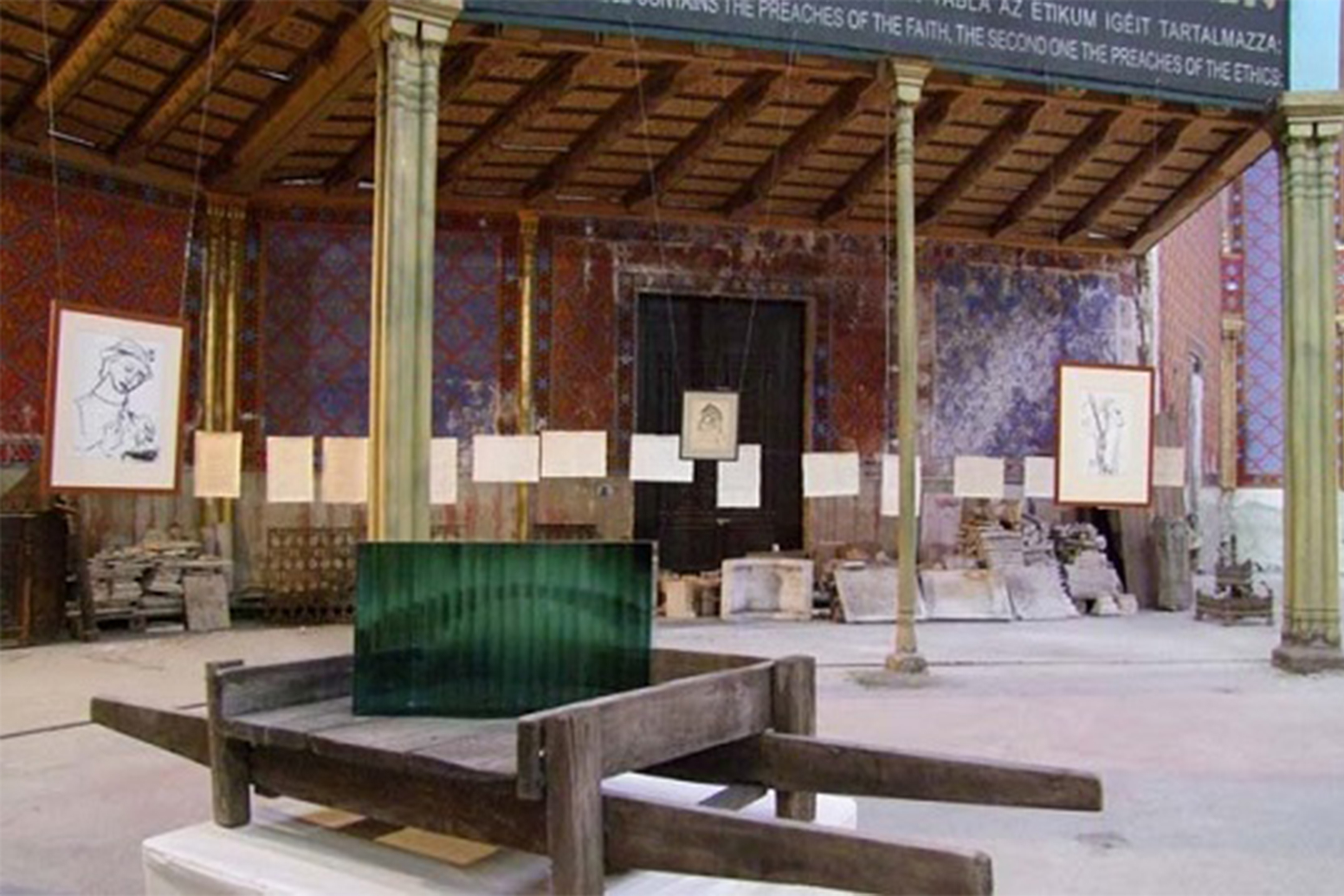

How the world preserves his memory

His first memorial exhibition was held at the Hungarian National Gallery in 1958, and then his paintings were also presented in Szeged, Pécs and Győr. On the 100th anniversary of his birth, an exhibition was organized in his honour at MODEM in Debrecen. On the occasion of the 105th anniversary of the birth of Imre Ámos, the Imre Ámos and the 20th Century – a Contemporary Art Exhibition (”Ámos Imre és a XX. Század – kortárs összművészeti kiállítás”) was organized at the Old Artists’ Colony Gallery in Szentendre and the Contemporary Hungarian Gallery in Dunaszerdahely.

Most of his works are exhibited in Szentendre, as part of a permanent exhibit at the Imre Ámos-Margit Anna Memorial Museum. His works can be seen at the Imre Ámos Gallery in his hometown of Nagykálló, as well as at the Deák Collection in Székesfehérvár and at the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest.

Early years

Coming from a Jewish family in Nagykálló, Ámos was deeply influenced in his childhood and early youth by his Talmudist grandfather, who also passed on extensive secular knowledge to his receptive grandson as a teacher. He moved to Budapest in 1926, where he studied engineering until the age of 22, but he felt fascinated with drawing and painting. Therefore, he left the technical university and applied for admission to the College of Fine Arts, where he became a student of Gyula Rudnay between 1929 and 1935. He was able to exhibit very early; his picture Women Dreaming (Álmodó asszonyok) won first prize in the Spring Salon of the Szinyei Society in 1934. In his early years, Rippl-Rónai’s ‘plane compositions’ from Paris influenced by Art Nouveau, and Róbert Berény’s dissolved decorative painting in the 1930s served as a model for him. He was strongly influenced both spiritually and emotionally by the fate of his fellow painter Gyula Derkovits as well as by his spiritual paintings. In any case, it took Ámos only a few years to develop his own style.

A gift from life: the influence of Paris and Chagall

The art of Marc Chagall, a painter genius born as a Hasidic Jew from Vitebsk, had been known and followed by Amos since his youth. In 1936, he placed a self-portrait below a portrait of Chagall. Their figures are accompanied by the characteristic Jewish building silhouettes of their birthplaces. The dual hand motif of the Cohanite blessing acts almost as a sign of Amos’s loyalty till death. It is no wonder that he and his wife, Margit Anna went to Paris to meet Chagall when they managed to gather enough money for their first trip abroad. The short studio visit on the 4th of October 1937 remained the most important event in Amos’s life, the details of which are known from his long diary entry. The two poor Hungarian painters also showed their works to Chagall, who had become world-famous by then, and received them with benevolent courtesy. Lacking money, they could only stay in the capital of European modern art for less than three months, at a time when surrealism was in its heyday and Picasso was at the height of his career – even thought the stay was shorter that they might have liked, they returned home with deep impressions.

Although Amos’s art is similar to Chagall’s in terms of its Jewish origins and symbolism, its nature is decidedly different from that of Chagall’s, who recalls Vitebsk and the folk figures of the former rustic Jewish world in a liberated way, with playful nostalgia. Coming from a much harsher Hungarian reality, Ámos struck a more tragic tone: he experienced Jewish life as a biblical fate, a constant existential threat. He called his increasingly visionary style ‘associative expressionism’, with increasingly common Jewish themes and motifs after their moving to Szentendre in 1938.

Gory times

In 1937, Lajos Vajda invited Ámos to Szentendre, where he found a company of like-minded. However, his living conditions there remained miserable and his situation was hopeless. Poverty, artistic-professional isolation, a suffocating political atmosphere, and the threat of an impending war made his painting more and more exalted and visionary. He used symbols more and more often: he drew not only from the Jewish tradition (shofar, candle), but also from Christian art (angel with a sword, olive branch, etc.) A typical example of this era is a double self-portrait called Waiting for Dawn (Hajnalvárás), in which he and his wife dream of a better future, symbolized by a green leafy branch and a huge red rooster. The motif probably dates back to the 19th century and originates from the ‘miraculous rabbi’ of Kálló, who provided the famous lyrics for the most beautiful and painful Jewish folk tune to this day, The Rooster is Crowing (Szól a kakas már…) a Hungarian folk song from Szatmár. This may be the reason why Ámos included him in his 1938 painting Dreaming Rabbi (Álmodó rabbi), among several other pictures.

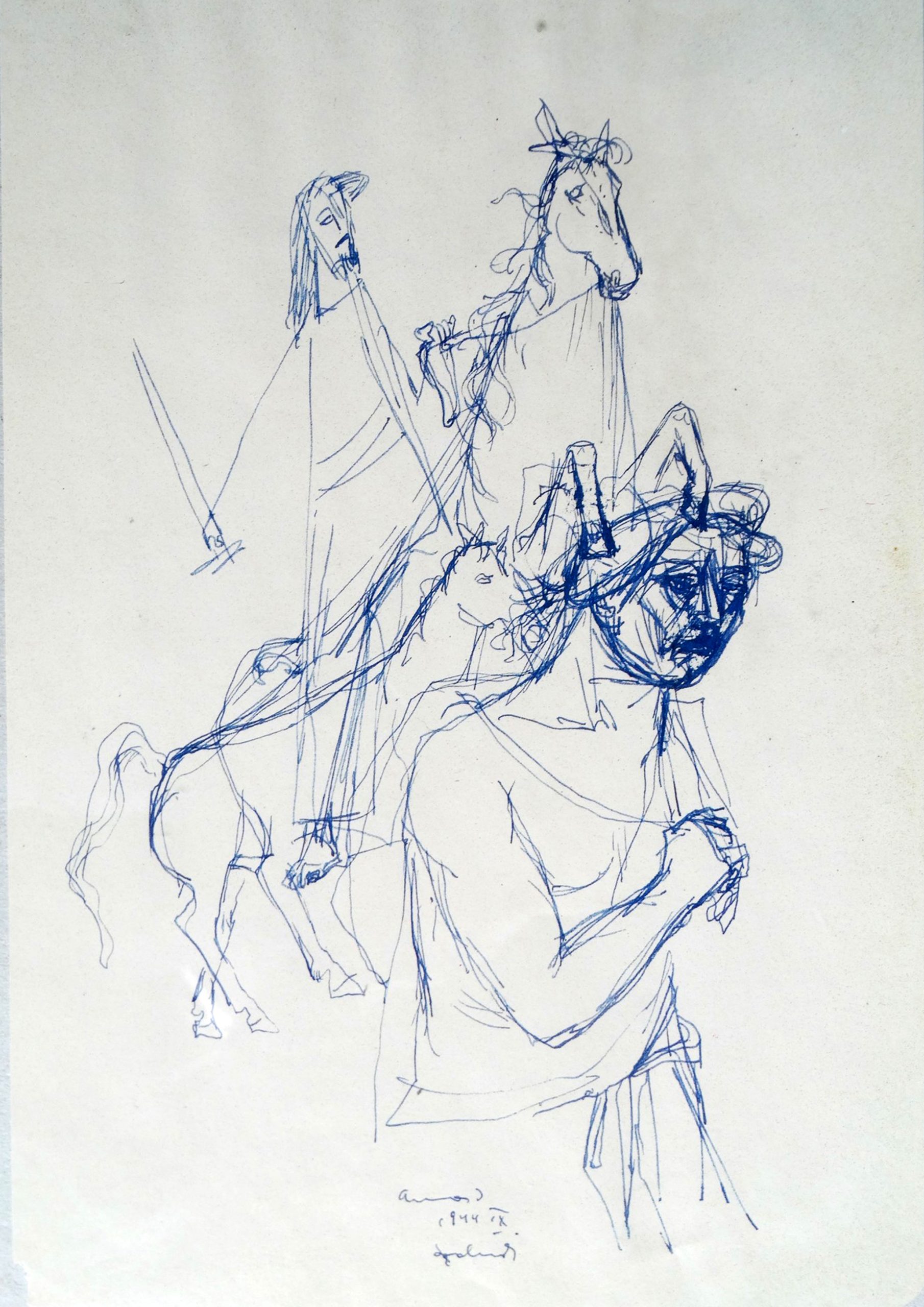

The Apocalypse series and the Szolnok sketchbook

The pinnacle of Ámos’s graphic art is the Apocalypse (Apokalipszis) series created in 1944, the year of the German occupation and the Hungarian Holocaust. It is a shocking actualization of John’s Book of Revelations in the New Testament. He uses the universal language of Judeo-Christian symbolism to speak of the universal destruction of Satan, but also of the hope of salvation from horrors.

Imre Ámos spent the last months of his life in a labour camp in Szolnok, from where he was deported to Thuringia, where he died under unknown circumstances. His last “work” was a spiral bound booklet that he was able to pass on to his wife, Margit Anna, in 1944. During the most difficult period of his life, he created drawings using blue and red ink in it. The so-called Szolnok sketchbook (Szolnoki vázlatkönyv) could almost be a fine art counterpart to Miklós Radnóti’s ‘Bori notebook’: memories of camp life, family and natural idylls, symbols of a candle going out, a falling angel, an untangled life thread, fire-water, and a cosmic-sized monster head are lined up in an unedited form in nearly forty feather drawings. In the last drawing in the booklet, an icon of the suffering of the innocently crucified Jesus appears.

1907.12.7 – 1944