1901

Born on April 17th in Terézváros, Budapest to Adler Márkus Joel, a baker’s assistant, and Terézia Kohn of Jawonik, Galicia. By the time little Zsi – as he was called by his parents – had grown up, the Hungarians had already stamped their mark in the history of the modern Olympics with the championship titles of Alfréd Hajós and Rudolf Bauer.

1912

Although he came from a large family blessed with many brothers and sisters and had countless friends, the boy was often beaten up on the grund by “enemy gangs” because of his small stature and weight.

1919

A friend put an end to this problem when he took Adler to the Gymnastics and Fencing Club in District III and enrolled him in boxing classes. Blessed with a devilish sense of rhythm and agility, the youngster weighing a mere 50 kilograms caught the attention of his coaches early on.

1923

The first major sporting event after World War I was the Budapest Championships on 1 April, where champions were crowned in eight weight categories. It was here that he first appeared in TVE colours, and won the featherweight category.

1924

The international meetings that would become a tradition, starting with a series of matches against Austria, commenced this year. The Hungarian team consisting of Adler (Sas – English: Eagle), Erdős, Vörös, Löwig, Untenecker (Alszegi) and Osztermann won 10-2.

1925

He was a boxer of the Budapest Athletes’ Club (BTK) when he won the Hungarian national featherweight title. In the same year he was a member of the Hungarian team at the first European Boxing Championships in Stockholm.

1927

In addition to competitive boxing, he soon took on coaching duties at his club.

1928

He won the Hungarian team championship title with the Budapest Athletes’ Club. He retired from boxing in the same year, at the age of 27; he continued his career as a trainer.

1930

The 1930s were a crucial period in the history of Hungarian boxing, as Budapest was awarded the right to host the European Championships by FIBA. He worked first as a coach of the Hungarian national boxing team at the BTK, later at the European Championships, then at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles and Berlin. The national championship was also a qualifier for the European Championships. The squad started preparations under Adler’s supervision. According to the press of the time, “the army of Angyalföld achieved a success that attracted everyone’s attention. It has beaten Europe and dazzled the world.”

1932

The team selected for the Los Angeles Olympics were coached by Adler and Steve Klaus. Only three competitors travelled to the games: Énekes, Kubinyi and Szigeti. Unfortunately for Kubinyi, he suffered a serious ear infection and underwent surgery immediately after their arrival. However, after Antal Kocsis’s 1928 victory in Amsterdam, István Énekes won the second Hungarian boxing gold medal in the history of the modern Olympics.

1940

To enhance his skills, he obtained a master’s degree in boxing from the College of Physical Education (TF).

1948

After the dissolution of the Budapest Athletes’ Club, he worked as a coach first for Vasas and then for Újpest Dózsa until 1970.

1952

He was the head coach and captain of the Hungarian national boxing team until 1972.

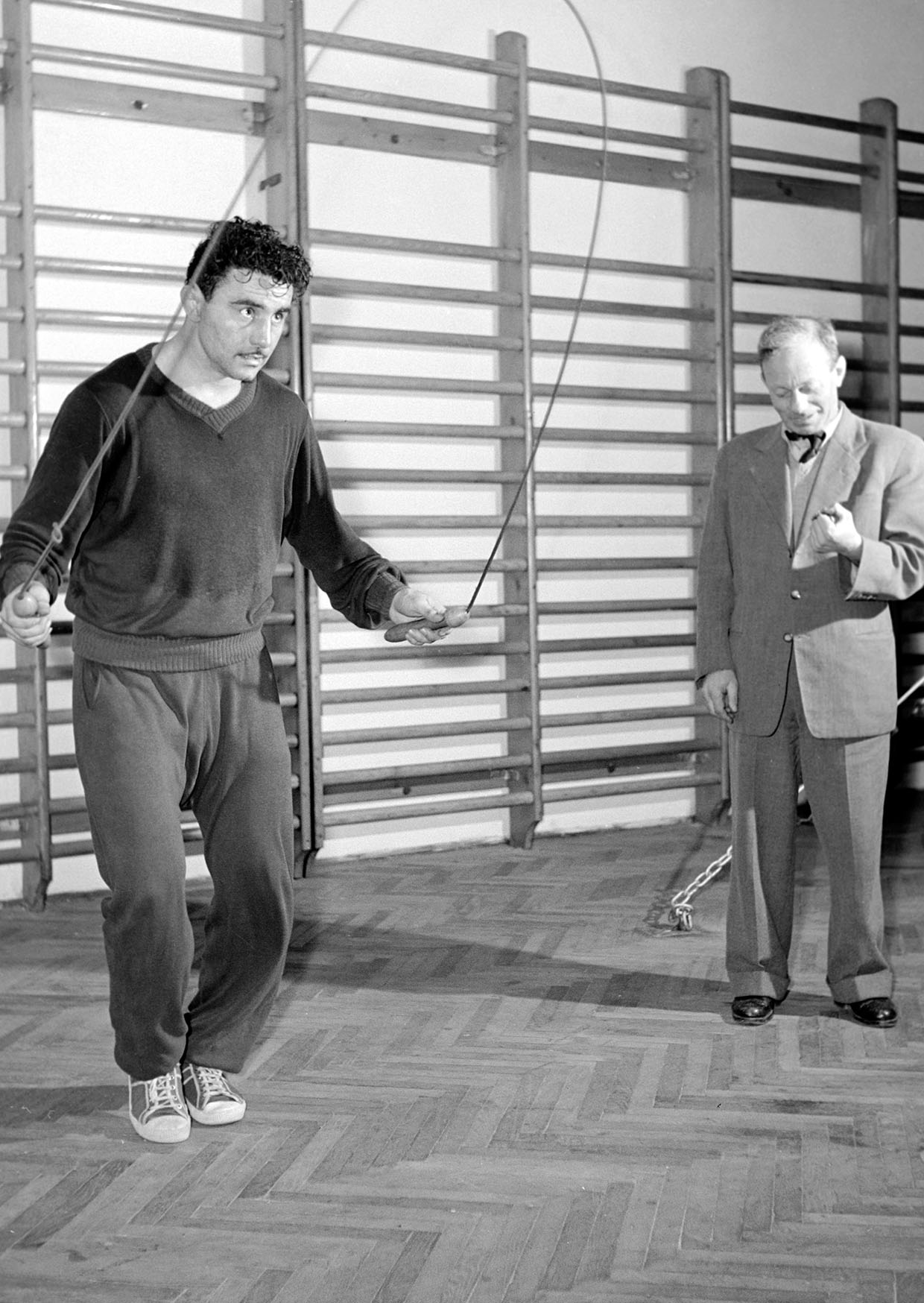

1953

He coached the remarkably talented László Papp for nine years; but he also stood in the corner with the likes of István Énekes, Imre Harangi, Gyula Török, János Kajdi, György Gedó and Tibor Badari.

1958

The Hungarian Council for Physical Education and Sport was established for the unified management of physical education and sports activities, and Adler was twice elected a member of the Council.

1961

The Hungarian Council for Physical Education and Sport was established for the unified management of physical education and sports activities, and Adler was twice elected a member of the Council.

1961

Zsigmond Adler was one of the first in Hungary to qualify for the title of master boxing coach, along with the likes of Miksa Bondi and Imre Szántó. Adler was awarded the Gold Medal of the Sports Merit of the Hungarian People’s Republic for his many years of outstanding performance in sport.

1969

Together with László Papp, he was asked to lead the national team, which marked the beginning of another golden era for Hungarian boxing.

1972

The national team returned home with four medals from the Munich Olympics. Following that, the ageing coach retired for good.

1982

Zsigmond Adler died on February 12th at the age of 80. He was laid to rest in the Farkasréti cemetery.

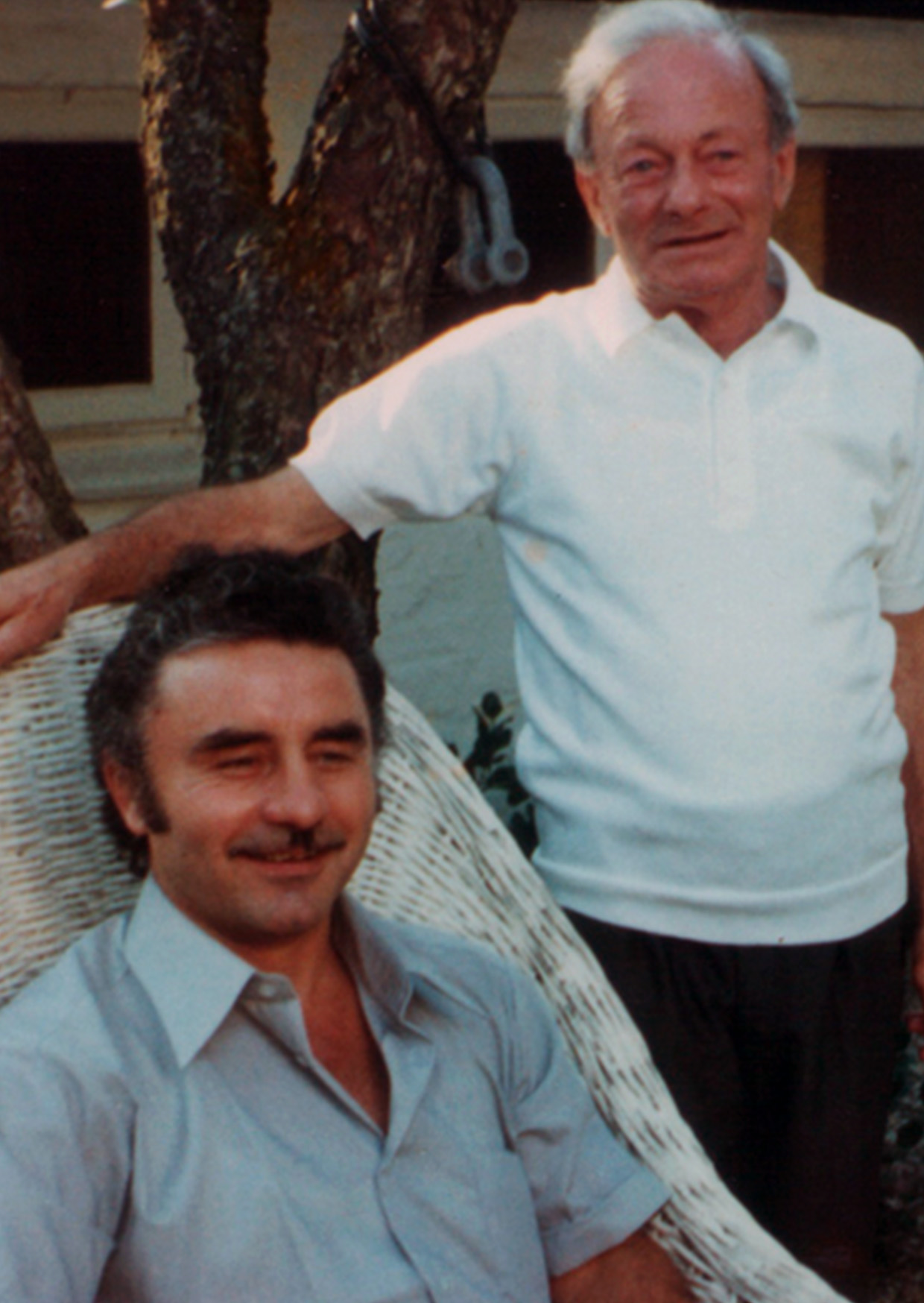

When he first met Laci Papp, neither of them took the other seriously

Adler’s most successful pupil was three-time Olympic champion László Papp, whose training he oversaw from 1953 to 1962. The coach first met the then 20-year-old Laci Papp after World War II, an encounter he later recalled as follows: “I met Laci in 1946, because at that time I was also going down to the Vasutas club. I was asked to look at a kid to see if he showed any promise. It takes a lot to become a great boxer. I didn’t think Laci had these virtues at the time. He was a boy with great punch, good reflexes and excellent passive resistance. (…) The truth is that he didn’t take me seriously, but I didn’t take him seriously either!”

Adler was not allowed to travel abroad until 1956

The Hungarian authorities received a letter from Steve Klaus, a Hungarian-born manager living in Italy, asking Adler which Hungarian boxer he considers as one showing potential. All this happened just before the 1948 London Olympics. The rumor that the coach wants to sell Hungarian boxers abroad spread like wildfire. As punishment, Adler was not allowed to leave Hungary until 1956.

He also had problems with travel later

Adler’s coaching career has not been without its ups and downs. Because of his conflicts with the Hungarian sports administration, he was refused permission to travel to major international competitions on several occasions, which is why he could not lead the Hungarian national boxing team at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

His character appeared in a Hungarian novel

The figure of Zsigmond Adler appears anonymously but recognisably in the first part of Vilmos Kondor’s series of historical crime novels, Budapest noir, published in 2008, which documents Budapest between 1936 and 1956. “Set in a politically turbulent time, the story follows the work of a jaded but tough reporter as he asks a series of unanswered questions about the seemingly trivial, open-and-shut murder case of a young Jewish girl, who was beaten to death and left in a courtyard,” – the blurb says.

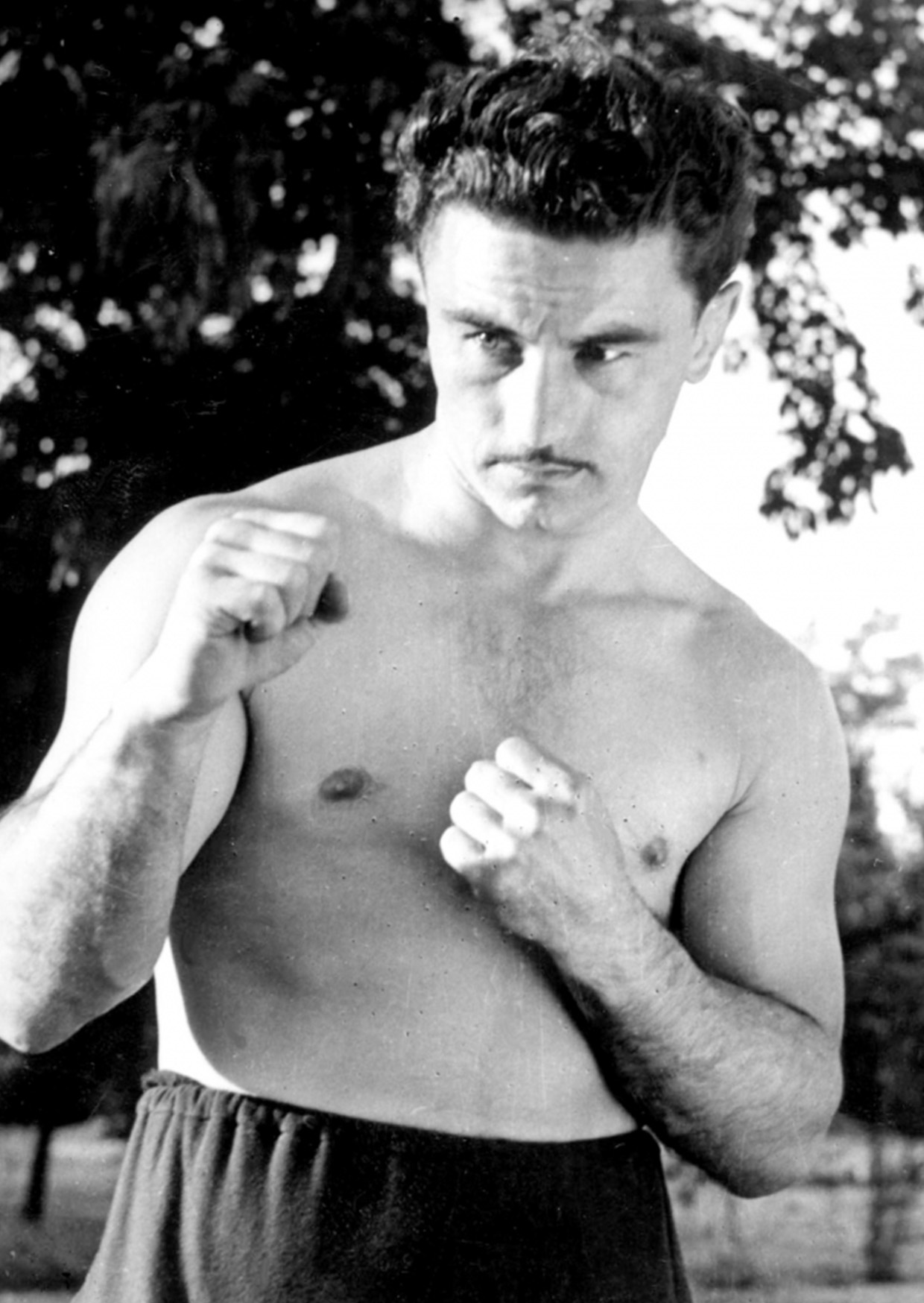

He had an instinctive talent for teaching

In today’s terms, he started boxing late, at the age of sixteen, but this was not a disadvantage at all in the early 20th century. Back then, it was the way things worked, since almost any suburban kid had the stamina for the sport. Adler was taught to hit strong and fast. Over time and through his own experience, he has learned not to rush. Before delivering the “strong hit”, he should play slowly and smartly. According to his students, he probably knew everything about boxing. He was barely in his twenties when he was already practising basic moves and punches with youngsters interested in boxing. He started training instinctively and with good intentions, which later became his profession when he became disillusioned with the competitive world after eight years of boxing. He did not deny that he would have liked to teach everyone to box: “We have to produce not only champions, but also healthy, strong, trained people.” He welcomed everyone interested in boxing, even if they did not show talent, but he always let everyone know what they can expect from the sport. He did not punish pupil, but those who were relaxed enough to take time off from training had to make up for unjustified absence with hard work. Adler worked even during the Anti-Jewish laws and the Holocaust, although he was sometimes forced into hiding because of his origins. Boxing has become a way of life for him, a means of survival and a source of psychological regeneration. At the London Olympics, Adler was finally able to add an Olympic champion to Hungarian boxing in the person of Tibor Csík, a bantamweight boxer from Jászberény. Hungarian boxing owes this gold medal partly to Rudolf Kárpáti, who noticed in Belgium that Csík had first boarded a ship to Africa by mistake.

His student László Papp is still considered one of the greatest boxers of all time

The relationship between Papp and Adler was one of father and son, master and pupil. And how to box cleverly was something we could learn from Laci Papp’s fights. Adler was impeccably good at knowing when and with what instructions to send his pupils to the ring. He first scouted their opponent and built up a tactic against him: fast, effective footwork, with some hard punches in between the small, subtle hit, and preferably with quick series of punches. Adler “took over” Laci Papp when he was already a two-time Olympic champion, i.e. as an almost ready-made athlete, in 1953. Working together could have been easy, but the Communist party ranks made sure it was not. In 1955, Adler was punished by not being allowed to travel to the European Championships with his pupils. Expressing his anger, Papp also refused to travel. None of them were forgiven for this by the party leadership. The European champion was not allowed to fight for the world title in his weight class for political reasons that are still unclear. Adler wasn’t spared either: The Olympic team had to travel to Tokyo and Mexico City without him, so he could not be there for his students at critical moments, for which they paid a heavy price. The team departed from the Olympic Games with a quick defeat.

The most successful four years of Hungarian boxing

The most successful four years of Hungarian boxing – or, if you prefer, the golden age – came when the political leadership realised that expertise was needed: therefore Adler and Papp could now emerge from their enforced break as the coaching duo of the national boxing team. They complemented each other well as coaches and results came quickly. Within a year, the national team returned from the European Championships in Bucharest with two gold medals. And two years later, in Madrid, three gold medals, a silver medal and a bronze medal once again drew attention to Hungarian boxing. In 1970, the European Junior Championships brought the sport a stunning success counting five gold, two silver, and two bronze medals. In the history of Hungarian boxing, at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, three competitors reached the finals for the first time, while their fourth colleague finished with a bronze medal. The finals ended with one gold and two silver medals. The First World Amateur Boxing Championships were held in 1974. However, the old master had an argument for inexplicable reasons with Papp, which left a deep mark on their flourishing professional collaboration, so much so that Adler eventually refused to travel with the team to Havana and retired from the profession altogether.

1901.4.17 – 1982.2.12